Revenue Recognition Frauds for Lawyers: Percentage of Completion

Revenue recognition is a central accounting principle that dictates when a company can record a sale and recognise revenue. Revenue is often used by internal and external stakeholders as a metric to determine a company’s worth, but if revenue recognition is deliberately manipulated, the fraud can carry financial, reputational and legal consequences. This article is part of a series explaining some of the most common forms of revenue recognition frauds. See here for an overview of revenue recognition and the potential consequences of its abuse.

-------------------------------------------------------

What is percentage of completion (POC)?

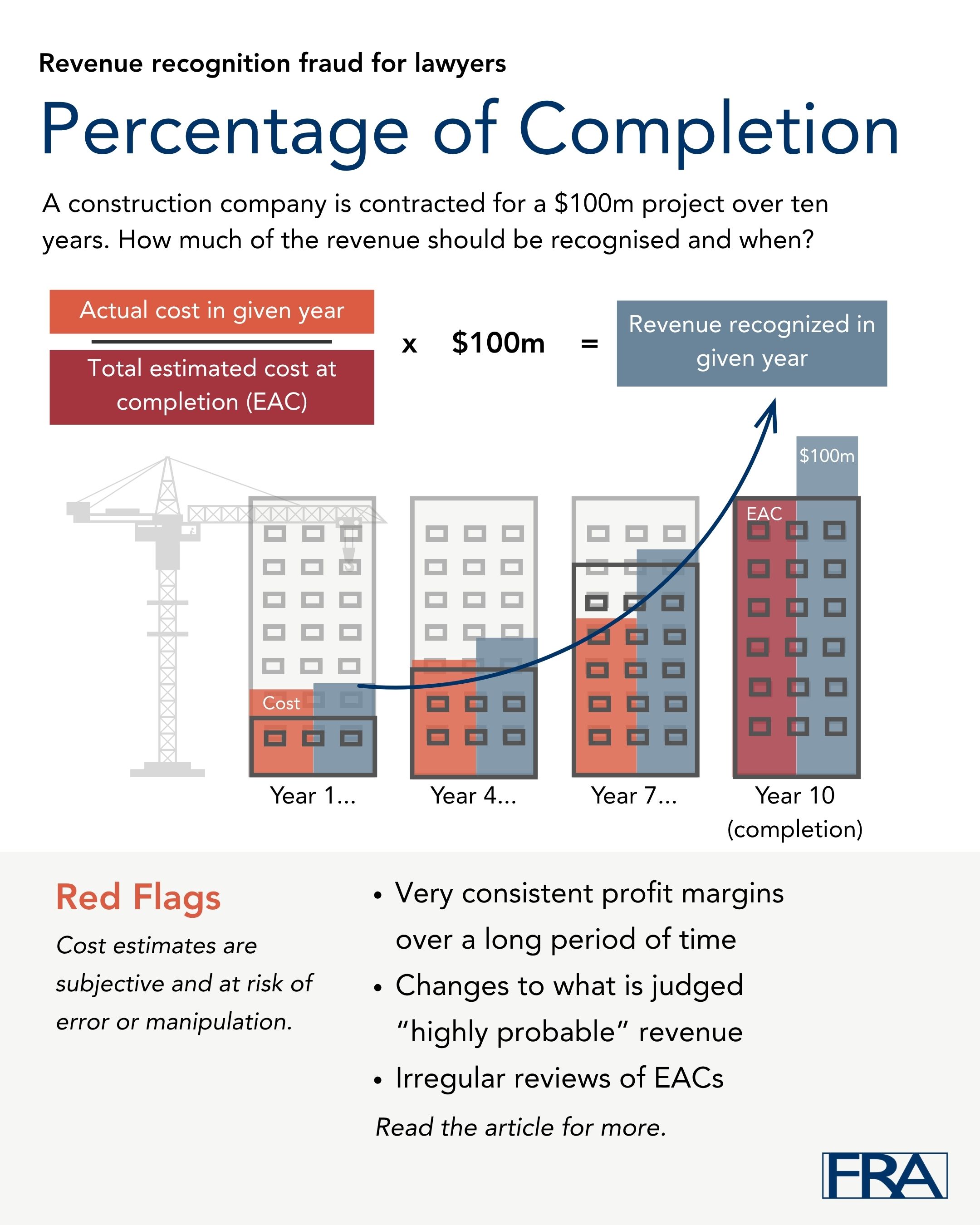

Percentage of completion is a method used by companies to gradually recognize revenue over the duration of a long-term project, such as a large scale construction, based on the extent of work completed rather than all at once upon project completion. The POC method relies on a number of inputs including resources consumed, labour hours expended, and time elapsed, but the most common approach compares costs incurred to total estimated costs at completion. However, cost estimates require subjective judgement, so there is a risk of error or manipulation that would alter revenue recognition. This article breaks down how POC is determined using estimated costs at completion, provides practical red flags to watch out for, and details investigative steps for counsel and forensic teams.

How it works

Take for example a construction company that has been contracted to build a bridge for $100m over five years. How much of the $100m revenue should be recognised in each year?

The POC method compares actual costs incurred in a given year against estimated total costs at completion to calculate the project’s progress and recognise the correct proportion of the $100m revenue, see this calculation below:

Errors in parts (a), (b), or (c) of this equation would alter the amount of revenue recognised. Estimating costs years into the future requires a lot of judgement, increasing the risk of errors and intentional misstatements (learn more about accounting judgements [here]). Furthermore, this process is repeated at least once every reporting period, creating more opportunity for misstatement. If there is a misstatement, the question is then whether it arose from misjudgement or fraud?

One issue that often arises in relation to the POC method is onerous (loss-making) contracts. As soon as a contract is deemed to be onerous, a provision must be recorded for the total loss projected to be made on the whole contract.[1] When it comes to long-term contracts, this can create significant costs booked in the current reporting period and a corresponding impact on profit, which creates the incentive to preserve the forecasted profitability of a project by manipulating the estimated revenues and/or costs at completion.

Subjective elements in POC calculations liable to error or manipulation

Anticipated vs additional costs – impacting part (b) of the above equation

At the beginning of a long-term contract, a baseline estimate of costs at completion is created which is then used as a comparator for all progress updates against the estimate. In each update it is important to assess whether costs incurred since the previous update were anticipated in the baseline estimate, or if they are unforeseen additional costs which might necessitate a reduction in the contract’s profitability if no additional revenues can be raised, e.g. via a variation order. Refusing to acknowledge costs as additional to the baseline estimate could improperly maintain the project’s profitability.

Risk contingency – impacting part (b) of the above equation

One common practice when estimating costs at completion is to include a risk contingency to account for the risk of potential additional costs crystalising. For example, a contingency is often included for the risk of liquidated damages triggered by delays. This is calculated by estimating the likelihood of a delay and the cost that would incur. This calculation could be manipulated by understating either the impact or the likelihood of the risk, or by excluding a risk altogether.

Accounting outside the POC calculation – impacting part (b) of the above equation

One method of improperly maintaining the profitability of a project is to book costs outside of the POC calculation, i.e. within non-project accounting records. This means that while the company’s overall costs may be complete, the profitability of the individual project is misstated with potential implications related to onerous contracts. This is a direct breach of the accounting standards.

Allocation of overheads – impacting part (b) of the above equation

In an example of a building development project, a company may be required to prepare a POC calculation for each building individually and therefore need to allocate overhead costs across all of the buildings. This allocation could be manipulated to protect the profitability of specific buildings and prevent them becoming onerous.

“Highly probable” revenue – impacting part (c) of the above equation

When estimating revenue at completion, future revenue can only be included if the contract is approved and the amount of revenue is deemed to be “highly probable”.[2] For example, management may consider a contingent fee as highly probable, or it may be considered highly probable that a contract amendment increasing the project’s revenues that is still under negotiation will be signed. The definition of “highly probable” is subjective and therefore offers a chance to overstate future revenue by employing a looser interpretation of the standard.

Red flags

The following red flags might warrant an independent forensic investigation to determine if the POC calculation is being manipulated.

Accounting and financial red flags

- Very consistent profit margins over a long period of time, particularly in a time of fluctuating costs and delays, could be a red flag that the POC calculation is being manipulated to maintain the margin approved in the proposal process.

- Proportionally low value risk contingencies, or contingencies that never adjust the likelihood of crystallisation.

- Projects that are barely profitable could be a red flag that the POC calculation is being manipulated just enough to avoid the impact of an onerous contract.

- If a company is running multiple POC calculations, such as in the building development example earlier, this provides more opportunities for manipulation.

- Changes to a company’s accounting treatments such as how the company interprets “highly probable”.

Operational red flags

- Lack of communication between the sales team and the accounting team could lead to a project being accounted for according to optimistic commercial projections as opposed to an appropriately prudent approach driven by the accounting standards and the reality on the ground.

- Poorly documented POC processes or a lack of supporting documentation for estimates of revenue or costs at completion.

- Irregular, or rare, reviews of the estimated costs at completion. The reviews would ideally also be both bottom-up and top-down.

- A tone from the top focussed on unrealistic profitability targets or an obsession with short-term financial results.

The nuances of POC investigations

An investigation into a POC calculation has similarities to other revenue recognition investigations including analysis of accounting data, review of contemporaneous correspondence, and interviews with employees. However, there are two areas in particular where an POC investigation can be different.

Misjudgement vs fraud

Estimating revenues and costs at completion involves a significant amount of judgement, so it is always possible that a misstatement is simply a result of misjudgement as opposed to fraud. Having established a misstatement, an investigation should focus heavily on determining whether the judgement call was made in good faith given the contemporaneous information or if there is evidence it was a deliberate attempt to manipulate the POC process.

Change in estimate vs error [3]

In the context of POC calculations, this is relevant when a review of estimated costs at completion finds a prior year estimate is misstated. This misstatement could have been the result of an error, or it could be because there is new information that was not available when the prior year estimate was calculated. The latter would mean a change in estimate. A material error would require the prior year figures to be restated in the subsequent financial statements with accompanying disclosures, whereas a change in estimate only requires adjustments to the accounts in the current reporting period. Restatements can have significant consequences so an important part of a POC investigation is determining what data was available contemporaneously and what data has come to light since.

Summary

POC calculations are a complicated area of accounting made even more contentious by the amount of judgement required. Unfortunately, this opens the door for bad actors to take advantage of grey areas in the standards. This makes it even more important for external and internal advisors to be able to spot the red flags and investigate where necessary. If the risks can be understood then they can also be mitigated through appropriate policies and controls.

---

Learn more about other common types of revenue recognition fraud:

.webp)

.webp)